Beginning snippet:

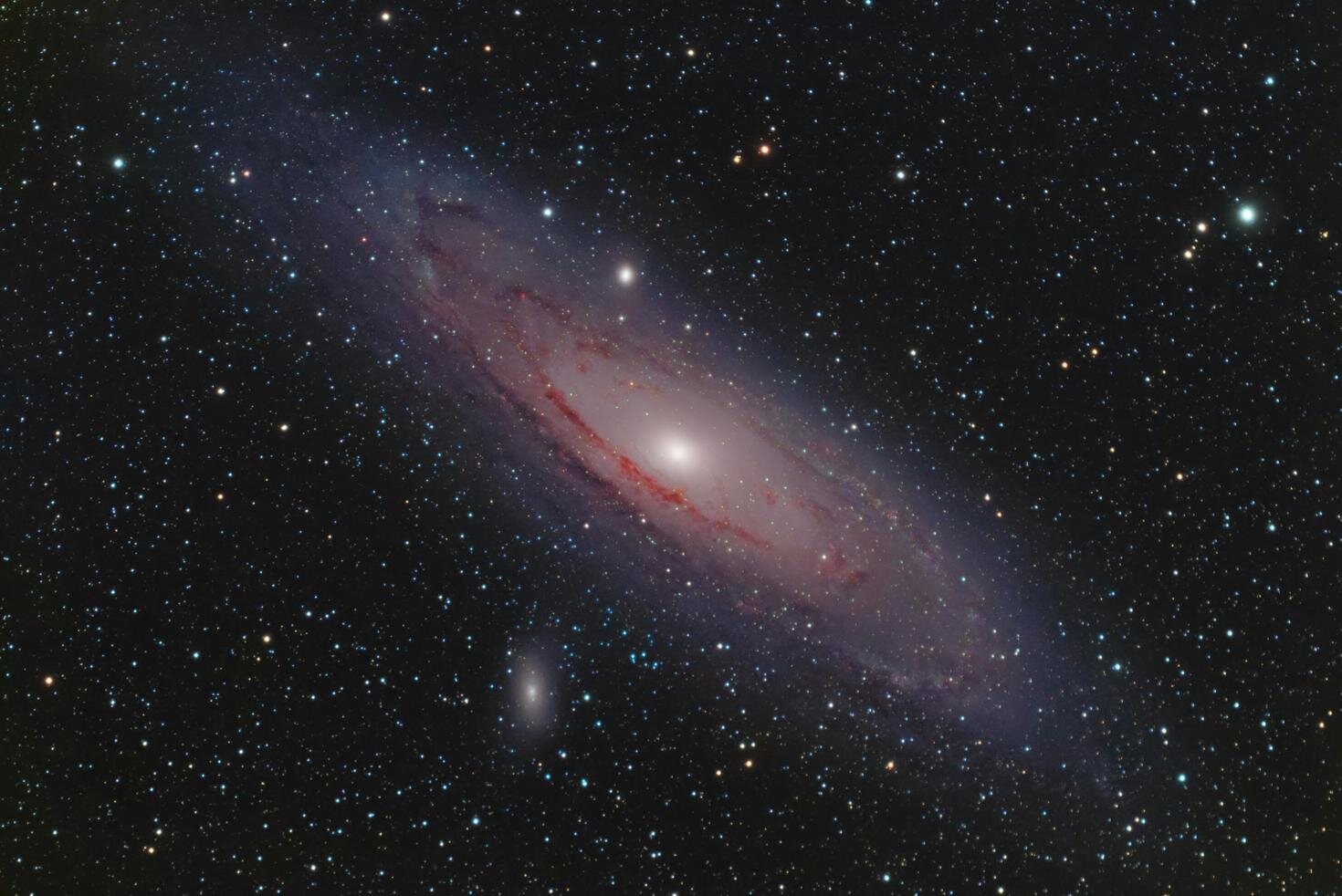

Led by Rajendra Gupta, adjunct professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Ottawa, the study asserts that if the basic strengths of nature’s forces (like gravity) slowly change over time and in space, they can explain the strange phenomena we observe, such as the way galaxies evolve and spin and how the universe expands.

The study, titled “Testing CCC+TL Cosmology with Galaxy Rotation Curves,” is published in the journal Galaxies.

Challenging established concepts

“The universe’s forces actually get weaker on the average as it expands,” Professor Gupta explains. “This weakening makes it look like there’s a mysterious push making the universe expand faster (which is identified as dark energy). However, at galactic and galaxy-cluster scale, the variation of these forces over their gravitationally bound space results in extra gravity (which is considered due to dark matter). But those things might just be illusions, emergent from the evolving constants defining the strength of the forces.”

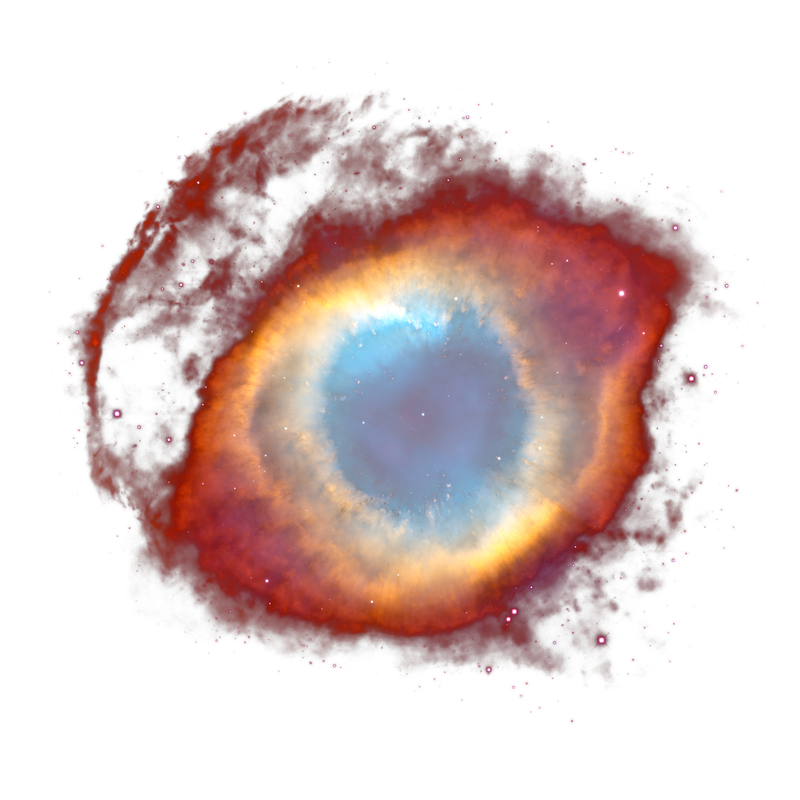

He adds, "There are two very different phenomena needed to be explained by dark matter and dark energy: The first is at cosmological scale, that is, at a scale larger than 600 million light years assuming the universe is homogeneous and the same in all directions. The second is at astrophysical scale, that is, at smaller scale the universe is very lumpy and direction dependent. In the standard model, the two scenarios require different equations to explain observations using dark matter and dark energy. Ours is the only one that explains them with the same equation, and without needing dark matter or dark energy.

“What’s really exciting is that this new approach lets us explain what we see in the sky: galaxy rotation, galaxy clustering, and even the way light bends around massive objects, without having to imagine there’s something hiding out there. It’s all just the result of the constants of nature varying as the universe ages and becomes lumpy.”

A provocative thesis from The Death of the Dark Energy Idea argues that dark energy may be an artifact of how we’ve mischaracterized photons themselves.

In the standard cosmological model, photons are treated as transverse electromagnetic waves. To explain the cosmological redshift, this model requires the expansion of spacetime—stretching the wave crests apart as the universe grows. Thus, the entire concept of “accelerating expansion” (and by extension, dark energy) arises as a geometric necessity of the transverse-wave assumption.

The book proposes a striking alternative: photons as longitudinal compression waves. In this framework, redshift emerges naturally from the wave’s own dispersive behavior, without invoking a stretching universe. And interestingly, when the density and motion components of a longitudinal wave are mapped over time, they produce the apparent sinusoidal electric and magnetic field variations of a classical transverse electromagnetic wave. In other words, the traditional transverse profile may simply be the observable projection of deeper longitudinal dynamics. This reinterpretation replaces cosmic expansion with an intrinsic mechanical process within the photon itself — no need to invoke the idea of dark energy to explain anything.

To support a compressible aether model, the author also reexamines the Higgs mechanism.

According to mainstream theory, mass arises as particles interact with the Higgs field—an invisible medium mediated by the Higgs boson. But the author notes that this “field-interaction” picture effectively describes what would occur in any reactive, compressible medium. If matter resides within a dynamic aether, similar resistance and mass effects would arise without requiring an exotic scalar field.

From this angle, the Higgs mechanism might actually be indirect evidence for an underlying compressible aether. In that case, the Higgs field could represent a complex mathematical abstraction of a much simpler physical reality—a mechanical medium that generates inertia and structure.

The discussion extends to two-photon physics, where high-energy gamma interactions produce electron-positron pairs. Here, electrons are modeled as vortical density structures, positrons as standing-wave formations—offering a wave-based ontology for matter creation and annihilation that resonates with quantum field observations but restores intuitive mechanical causation.

I’m not really qualified to evaluate the merits here, but as a science-interested layman, I’d be glad to see an alternative to dark matter and energy. Setting aside the technical arguments, the dark matter and energy approach smells like questioning the observations when your theory doesn’t match observations.

I skimmed the paper for testable predictions, and nothing stood out to me. Fitting existing observations is a good place to start, but if the only prediction is that nobody will find dark matter or energy, things may remain undecided forever.

I’m in roughly the same boat. Dark matter feels like a rather convenient mathematical addition. Excited to see how other physicists respond!

My understanding is that “dark matter” is a placeholder for “things are behaving in ways that would be explained by additional mass, but we can’t see any additional mass” and “dark energy” is “the universe is not only expanding, but that expansion is accelerating, and we don’t know why, so we’ll call it ‘dark energy’ because energy makes things happen”.

This video is a great explanation from someone that was actually involved in dark matter research.

As a current PhD student, I am very skeptical of theories that present themselves as alternatives to dark matter.

Dark matter is a very successful model of explaining our universe, with a ton of validation through simulations that can recreate a lot of what we see.

Unless another theory can do that better than dark matter, it is hard to consider it favorably.

Does this hypothesis comes with some predictions that could be tested?

I’d need an explanation for gravitational lensing before I could begin to consider dumping dark matter. This might, so it’s at least interesting.

Gravitational lensing is pretty simple, no? Mass bends the path of light. When light is passing near a massive thing (star, galaxy), it changes direction. Then when we see that light, what we’re seeing is not only in a different place in the sky (probably behind the massive thing), but it may be distorted or enlarged because of the many slightly different paths the different photons have taken.

I think the point was we need an explanation for why we see the amount of gravitational lensing we do around distant galaxies if we remove the mass that is explained by dark matter

Sounds like the “tired light” hypothesis in different words.

“tired light”?

If I recall correctly, it’s the hypothesis that photons lose energy as they move through the universe, and that’s why more distant objects shift red.

EDIT: Publisher of the Galaxies journal is MDPI, which strongly indicates it is predatory.

Also, so fringe:

This article belongs to the Special Issue Alternative Interpretations of Observed Galactic Behaviors

Sounds like yet another variant of MOND. Can any astrophysicists chime in?

IIRC, dark matter at least have good background on introduction, like how it is differently distributed from normal matter - and some galaxies seem to have more of them. Handwaving them as different constant on different areas sounds… eh.

It does look like they publish a sketchy amount.

deleted by creator